The Cost of Metal

What becomes of the human toll behind the mining industry?

Candice Jansen hears from Ilan Godfrey, a photographer who brings our attention to the contemporary realities of mining in a changing South Africa.

The miner stands as a particular South African archetype of suffering. A poor black man, often rural in origin, whose plight in dank hostels away from family symbolised the underbelly of mining during Apartheid. The world of his burden became South Africa’s industrial legacy. But how do we imagine South African mining today? Ilan Godfrey’s photography series, Legacy of The Mine (2013) shapes a look at its peripheral effects. Ilan documents precarious lives set against the backdrop of a contentious industry caught within a difficult economy and he does this with a remarkable intimacy. About the role of photography in this, Ilan seemed even keeled about the craft, neither over thinking the practice nor underestimating its power. He had lived abroad studying photography, but his childhood in Johannesburg rooted his development in the arts and South African stories. I began our interview asking him about this.

Candice Jansen | Ilan, your father was a keen amateur photographer who seemed to have influenced you as a child. Take me back to some of these earliest memories. How did they inspire your choice to become a photographer?

Ilan Godfrey | I got a glimpse into the journalistic side of photography early on. We always had cameras and photography books around the house. I remember books like this (reaching for the book, In Our Time: The World Seen by Magnum Photographers 1989). Those experiences probably put something in my mind…like when my father used to take me along to this tiny little camera store in central Johannesburg called Fripps Photographic. As a young boy, I always used to be there, you know–bored–standing around watching the photojournalists come in. These were established photographers from The Bang Bang Club documenting South Africa at the time.

So how did you get serious about photography?

In 1999 after I matriculated from high school, I left South Africa with a very basic portfolio of images. I ended up working behind the counter at a photography store in London thinking it could be an opportunity for me to learn from photographers. I saved a little and was surviving in the UK when I started traveling. I went to Asia for a bit; saw some of Europe, but always with my camera. I wasn’t thinking too much about why I was photographing. I was just doing it quite obsessively…until I got to the point when I needed to make that leap and find a direction to go in.

You needed to find your subject?

Yes. I needed to know what I was doing with this medium…so I enrolled in a degree programme and was drawn to documentary photography…drawn to storytelling and building narratives with images…I thought of doing stuff in the UK, but there was something about returning home and witnessing what was happening back in South Africa…

How did your interests in mining come about?

I didn’t want to do a project on mining itself. I made the move back to South Africa in 2011 to really understand the stories that I wanted to tell. I decided on mining amongst several I’d written into notebooks and journals. Initially, my interest in mining came from its environmental impact. Having grown up in Johannesburg, I didn’t really take a lot of notice of mining which is part of the landscape. You drive by these huge mines extracting whatever minerals they’re extracting, never really thinking about the hidden stories of these places. I think it was something about wanting to step outside those confines of urban Johannesburg and go out into the rural, smaller towns on the periphery.

So having followed your interests, what do you make of mining?

Mining isn’t sustainable, we’re all well aware of that, but at the same time we’re reliant on it. We can’t turn our backs on that. While mining helped build Johannesburg, it also sustained Apartheid. So, while things have changed, the mechanics of cheap labour are still in place…so we should keep asking what happens to people who work on mines? What compensation do they get if they get ill? What are the communities relying on rural agriculture and cattle farming going to do when their rivers and lakes are polluted by toxic water?

These communities you speak of and have spent time with, how do they see mining and its legacy?

Even though I tend to not want to influence people by my questions…generally, I find there is concern; generally, people feel left out of the process that benefitted only a few…which is why I include community voices in my work with the use of extended captions. I wanted to share their concerns with a wider audience. And so I needed to be accurate in what I was sharing because I’d record very delicate stories that would often involve complicated legal issues.

What do you mean by not wanting to “influence” people by your questions?

I mean when you’re out in the field you’re focusing on making photographs, but you also want to gather accurate information. What I prefer to do is put on my recording device and say, ‘tell me your story’ and get a fluid uninterrupted wording of that person experiences. They know what they want to tell me. They know what their issues are, what their story is, it’s not about me trying to unravel it or pin point certain things. …Let them say their piece if they feel comfortable doing it, you know what I mean?

I do. Guess that’s the documentary way with truth: recording reality, as it exists in the world. How would you define documentary?

I see it as long form storytelling, it’s slow journalism…you’re engaging with a subject over a long period of time. It’s not something you can undertake in a day. Documentary for me unravels layers within an issue and those layers may not have been visible on the surface to start with. You have to dig a little deeper which also really depends on access. At the end of the day, we need to witness something with our own eyes. We need to go there and see it…and if it’s not there that day, we need to go back again and again and again, until it’s there.

Time makes all the difference in making documentary. It creates space for serendipity…

Very much so. It’s a beautiful thing. That’s why I said that to you in the beginning about choosing not to work on projects in London. There I felt that lack of serendipity…Look, I was fortunate to have won the Earnest Cole Award and spend more time with this project…because financing documentary is also challenging…Ultimately, having more time is a wonderful way of working…that extra time just to wander around the town or drive up and down a street, pop into the local shops, chat to people and explain what you’re doing…It’s amazing what people will share with total strangers.

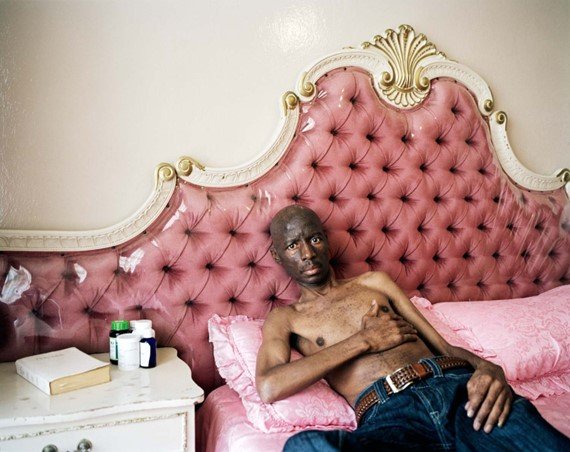

What did Mahlomola William Melato share with you?

I met many very sick men, like William living in small rooms at the back of houses…just forgotten. Charlie my contact person felt that it would be important for me to meet him. And William wanted to meet me having felt that his former employer had misrepresented him. He brought out documents that clearly stated that he had an occupational disease but when he applied for compensation, his management said he didn’t have an occupational disease…This is the case for a lot of men that work on these mines. When they get sick, they’re told to leave…William at that point when we met was very fragile. He was weak and very ill, as you can see in the photograph.

William lies atop such an ornate bed, in what I imagine was a bare room with only medication and a small bible by his bedside. His portrait has quite an emotional charge…

It was the first time in doing this project that I had a really emotional experience. It was a very sad meeting. I was quite moved. You know, you can’t sit there and sob, but you are affected, it does upset you…it makes me quite emotional now just thinking of how I sat listening to his story.

Audio Interview of William Melato (excerpt) from Legacy of the Mine by Ilan Godfrey. Released: 2012

He is very sick in his voice…that was one of the more challenging parts of doing this…because you want people to share their most intimate experiences of hardship. It becomes about more than just about making a picture, recording a story…With William there was a spiritual undertone…he kept saying ‘may God be with you on your journey’, ‘we need your voice’, ‘we need you to tell our story’…Does that make sense?

Yes, it makes complete sense. Documentary does affect you…and if it doesn’t, you’re probably not going deep enough.

********

BIO

Ilan Godfrey (b.1980) has a Masters Degree in Photojournalism from the University of Westminster in London, UK. Among several awards, Ilan has received the prestigious Ernest Cole Award in 2012 to complete his long-term project, Legacy of the Mine (2013) for which he was also awarded the POPCAP ’14 Prize Africa. Ilan has also exhibited in the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town, the Wits Art Museum in Johannesburg, and Musée du quai Branly in Paris.

Follow him on Instagram @ilangodfrey and view more of his work at ilangodfrey.com