The Work of Love Radio

How do we create stories that reflect the layered complexity of societies living in the aftermath of conflict?

Candice Jansen hears from Anoek Steketee, co-creator of Love Radio, an award-winning transmedia documentary project combining film, photography, audio, text and archive material to remind us of the complex process of reconciliation twenty-years on in post-genocide Rwanda.

What is Love Radio? At first glance–an online documentary that recreates the popular Rwandan radio soap Musekeweya (‘New Dawn’), a tale of love, hate, violence, and reconciliation between two rival villages that unfolds in seven episodes. Beneath the surface of this fictional story live unspoken, more complicated truths depicted with behind-the-scenes glimpses in film and photography, where citizens share the reality of their lives in Rwanda. There also is a supportive world of historical context in the form of an interactive timeline, map, and essays by journalists and academics. Not only is this story layered, it is also a device dependent digital experience. Smartphone users have their own version of short, more intimate vignettes of text and imagery of Rwandan stories.

Love Radio folds fiction with fact, implicating media and its manipulative power in the emergence of collective memory. Or so it says–questioning whether the idealistic veneer of fiction can foster reconciliation in a country still seeped in the very real trauma of its recent history. But this is not the Love Radio I asked co-creator, Anoek Steketee about. Instead, I was interested in her and partner Eefje Blankevoort’s process behind creating a pithy multimedia experience of such ambition. I began my conversation with Anoek by asking her to imagine meeting someone on the street who had just asked her, what is transmedia storytelling?

Anoek Steketee | Transmedia storytelling combines different forms of media into one story. But you have to be aware of why you’re using certain media to tell this story. You always should look to the content of your subject and then see what kind of medium is appropriate. Ask yourself for example why are you photographing something that you can also film? The advantage of transmedia storytelling is that you can tell a story in different layers. In Love Radio it was very important to use different layers: the idealistic layer of Musekeweya while at the same time revealing the behind-the-scenes layer with additional background information that represents Rwanda today. I also think that there is a danger to transmedia storytelling: The possibilities for using multimedia to provide information are never ending. You can put as much information online as you want, but we also didn’t want the viewer to get lost.

Candice Jansen | How did this multimedia world of Love Radio come about? Was the idea from the outset to create a transmedia project? Or did pieces emerge and you thought to execute them like this in the end?

We first went to Rwanda in 2008. We met the radio makers of Musekeweya and discovered the popularity of the radio soap–people on the street–everybody knows it. I’m a photographer and Eefje is a writer, so we did a story about this with photographs and text. But we thought about the topic and its many layers. Then we thought to create a photo book but to visualise a radiosoap is a big challenge for a photographer. The most obvious approach would have been to photograph actors and then to photograph listeners; but what would that then say about the radio soap itself? What would it say about contemporary Rwanda and about the country’s history? Then we thought we should use audio because it’s about radio. But if we’re going to use audio, why don’t we also use film? In the end, we knew we needed many layers and multimedia was the best way to put it all together.

It seems that photography did come first…

We started with photography but I became aware of its limitations…. You cannot tell every story by using photography. We actually wanted to mix photography and film in the online documentary but felt it made no sense to use film and still imagery. We found that for the rhythm of the documentaries it was better to use only film and then in other layers create slide shows of photography (used for the mobile and online version) and also use photography in the exhibitions as another form of understanding the story.

I also noticed the way you used language in your recreated radio soap. The narrator speaks English but other languages are used for dialogue…

Musekeweya has been broadcast since 2004, two times a week, so there are hundreds of episodes with 14 characters and we had to translate the original story within a story line of 20 minutes over seven episodes…. And so, together with Musekeweya script writers, we condensed it into only its key moments. The language used in the radio soap itself is Kinyarwanda because that is the language most people speak in Rwanda. We used our own narrator because we had to find a way to make this story understandable to a Western audience.

Was your primary intended audience Western?

Yes … but not only for Western audiences but a worldwide audience. The themes in this story are so universal: it’s about the influence of media on society, the emergence of collective thinking, and it’s also about scapegoating, about victims and perpetrators, about innocence and guilt…. I think every country, every society can learn from it.

Do you remember the first time you heard about the genocide in Rwanda?

I was in high school although the information in the beginning when the genocide started was very limited. Only after it already had taken place did information reach us via western media. The images we saw were mostly of refugees who fled to Congo but I remember it very well, I think everybody remembers it. It still is one of the tragic episodes from recent history. When we first went there in 2008–14 years after the genocide took place–after we landed in Rwanda, I remember having a very uneasy feeling…. I was nervous for having to experience the veneer of such a tragic past.

Was it like what you expected?

One the one hand yes, because the memory of the genocide is still so present, on the other hand, I did not expect to see a country so positive about the future, rebuilding so quickly. Kigali is growing so fast … I marveled at the difference in its development between 2008 and the last time I was there which was in 2014.

I want to return to the making of Love Radio. It has a very specific look that is consistent throughout the layers. How would you describe your aesthetic?

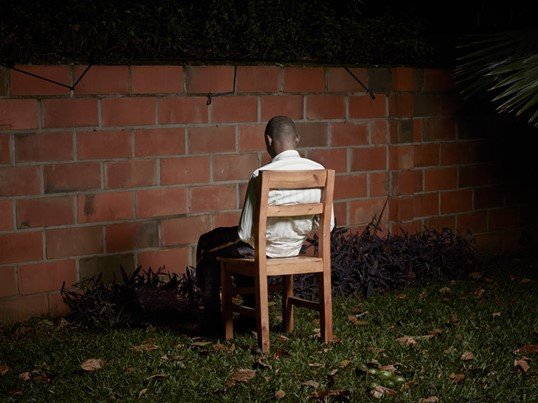

In general, I’m always trying to use the camera not only as a tool for documentary to raise social issues but at the same time, I also want to leave the viewer enough space for their own imagination by playing with light and directing people–not always but partly. I’m trying to create a sort of alienation…

‘Alienation’ could read as counter-intuitive for socially engaged documentary. It implies that you’re trying to create some kind of distance between what you are creating and the viewer?

Maybe I am. But I mean a distance that leaves enough room for people’s own interpretation … to somehow make it real that behind the surface of what we see, the beautiful surface, other realities may exist. Realities we don’t know, we don’t see, especially for an outsider. I’m always trying to play with that. To give the viewer a sort of alienated feeling, provoking them to think: ‘ok, there’s something going on with this image. I don’t know what it is but there must be a story behind it’.

I see what you mean … you’d sometimes photograph people from behind or use lighting that would be quite dramatic…

I always use lighting; in this case it was also very practical because I photographed people at night…

Why did you photograph people at night?

I wanted to photograph listeners at the broadcasting time of Musekeweya. This was the time when people were at home, sitting around the radio or walking on the street with their little phones listening to the radio … it’s also the time people are coming back from work.

Speaking of cellphones, in the mobile version, there’s no audio, only imagery and text in what you’ve called ‘Tap Stories’. Talk to me about the choice for how the project lives in mobile.

The mobile version has a very practical reason behind it because the website itself is too complex for mobile. We had to find a way to give viewers the opportunity to also experience the project on smartphones. Of course, you cannot compare the mobile version with the web version. They’re completely different. On the website, we created seven episodes and on mobile there are also seven different stories. That’s the only resemblance between the connected ideas on the two platforms. The stories for mobile are so simple and plain we thought it much more interesting to just have seven personal stories of people we met. There’s a story about the director of the radio soap; stories about actors, a listener, a human rights activist, all representing different voices from Rwandan society.

An excerpt from the mobile-only vignettes: Tap Story 7, A Love Story.

This project is also layered with collaboration. What about the partnership between you and Eefje? What do you each bring to the table?

In general we share the same interests in stories but we have different approaches. Eefje’s view on the world is more analytical or journalistic. My view on subjects is more poetic, even philosophical. I tend to work intuitively…. I think it’s a good combination. We provide each other context.

You complement each other in the ways you describe and it shows in the figurative and literal aspects of the execution. Astonishing to learn about the elements that have gone into such a tightly edited experience. Yet, if someone finds Love Radio online, without this insight, and explores the site, you could have no idea how deep the story goes.

Yeah, we wanted the viewer to decide for themselves how deep they wanted to go with the story. At first glance it tells a linear, almost fairy-tale narrative, retelling the original story of Muskeweya. The viewer can choose to stay. But the viewer can also choose to go deeper than the soap where happy endings predominate, and also see that reconciliation in real life is more intransigent.

Guess that’s what you meant when you said you wanted to “put the viewer in the director’s seat” with Love Radio, a real possibility of transmedia storytelling…

******

Bios

Anoek Steketee (b.1974) was born in The Netherlands and studied photography in The Hague and the Post-St. Joost in Breda. Her work has been featured at national and international festivals and exhibitions including solo exhibitions in the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam and more recently in ROSPHOTO State Museum in St Petersburg and the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam. She has completed commissions for the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam City Archives and the Tropenmuseum. In addition, her work has appeared in various international publications. She is represented by Flatland Gallery in Amsterdam.

Eefje Blankevoort (b.1978) was born in Canada and is co-founder of the journalism production company Prospektor. She is a writer multimedia documentarian. She has published Stiekem kan hier alles (‘Secretly everything is possible here’), about Iran, De Vluchtelingenjackpot (‘The Refugee Jackpot’), with photographer Karijn Kakebeeke) and Dream City (with photographer Anoek Steketee). Her films include Niemand vertelt mij wat ik moet geloven (‘No one tells me what to believe’), Joella, Best Friends Forever, and the interactive music documentary Hidden Wounds amongst others. Her work in progress includes the feature-length production Bring the Jews Home.